HIP-HOP AT 50:

LADIES FIRST

Hip-hop was no fad, and by the early ’90s, the rest of the world finally started giving in to what rap lovers had known for years. Yo! MTV Raps was at its height, smuggling hip-hop culture into suburban homes like a graffiti-covered Trojan horse; The Arsenio Hall Show did its part after hours. The Grammy committee nominated MC Hammer’s Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ’Em for Album of the Year, a first for rap. Sales had jumped from Run-DMC’s 3 million-selling Raising Hell in 1986 to Hammer posting over 10 million a mere four years later. Will Smith was yucking it up in prime time every week on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Hip-hop was here to stay—and so, without a doubt, was the female MC.

Hip-hop was no fad, and by the early ’90s, the rest of the world finally started giving in to what rap lovers had known for years. Yo! MTV Raps was at its height, smuggling hip-hop culture into suburban homes like a graffiti-covered Trojan horse; The Arsenio Hall Show did its part after hours. The Grammy committee nominated MC Hammer’s Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ’Em for Album of the Year, a first for rap. Sales had jumped from Run-DMC’s 3 million-selling Raising Hell in 1986 to Hammer posting over 10 million a mere four years later. Will Smith was yucking it up in prime time every week on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Hip-hop was here to stay—and so, without a doubt, was the female MC.

The male-dominated world of rap posed severe challenges for women artists, who at times seemed to face a choice between objectification and obscurity. Yet, as the decade unfolded, it became clear that there was room at the top for a range of female styles, from girl-power MCs to bling-dripping provocateuses to boundary-pushing eclecticists.

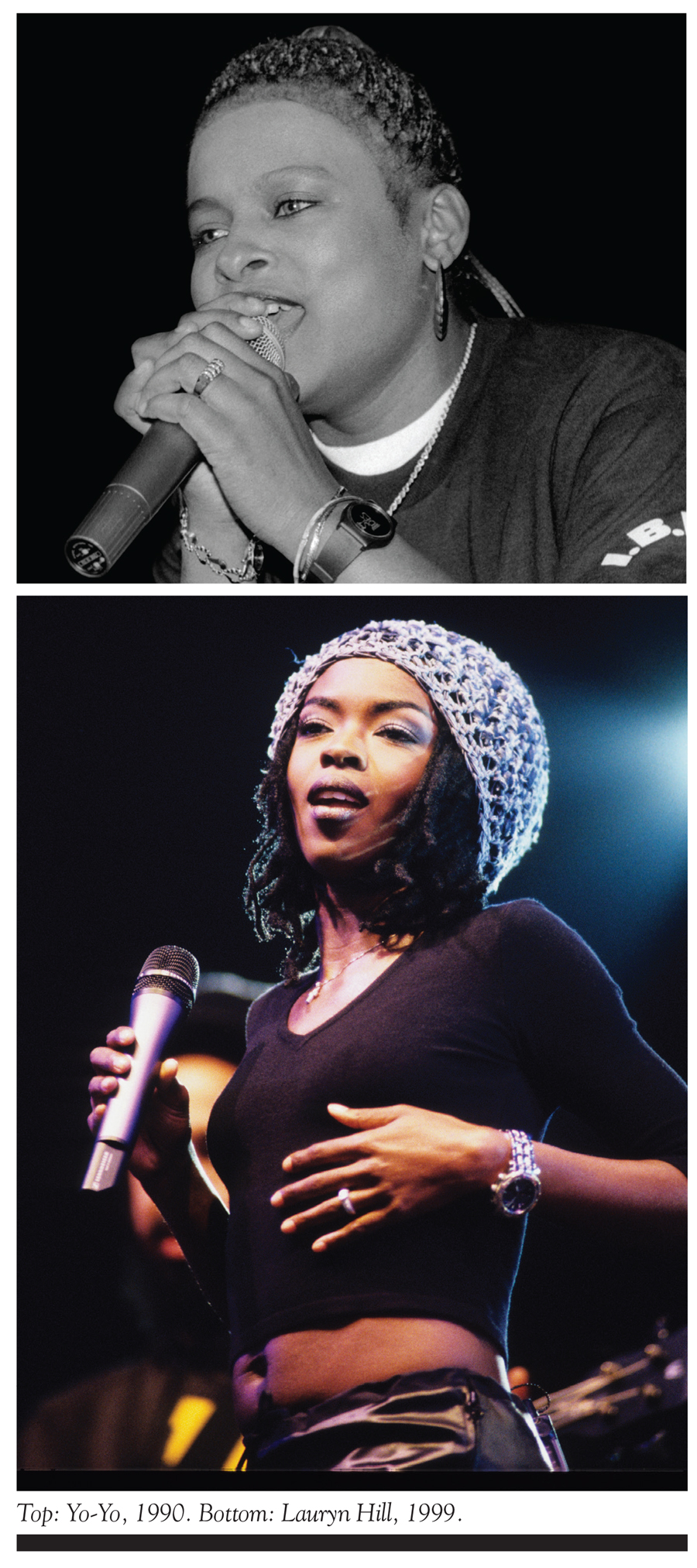

The social consciousness and Afrocentricity prevalent in the rap capital of New York City had segued into the hard-knocking gangsta nihilism favored in California. As N.W.A’s Dr. Dre took his solo turn with The Chronic in 1992, the earth-mother sensibility of Queen Latifah gave way to the Bonnie and Clyde gun-moll approach of Yo-Yo and The Lady of Rage. Still, the shift proved that wherever hip-hop was headed, women’s voices would be getting louder in the mix.

Sales spiked once rap spread to communities with deeper pockets than the hoods that gave birth to it, and Salt-N-Pepa were right there to share in the wealth, selling a million copies of their third album, Blacks’ Magic. Rich in cultural currency, the trendsetting duo, along with DJ Spinderella, offered sex-positivity on “Shoop” and “Whatta Man,” both of which became Top 5 Pop hits in 1993. Their videos, directed by fashion photographer Matthew Rolston, were full of bikinis, bubble baths, midriffs and Daisy Dukes. The pioneering trio reached a commercial height that year with Very Necessary’s 5 million copies, confirming an age-old mandate that has affected women in hip-hop forever: Sex sells.

The year 1988 means as much to hip-hop as 1967’s Summer of Love does to America’s rock ’n’ roll counterculture. At the forefront of women in rap back in ’88, Salt-N-Pepa followed the platinum success of their Hot, Cool & Vicious debut with A Salt With a Deadly Pepa. Rocking ripped stonewashed jeans, baggy T-shirts and cable-thick gold chains with door-knocker earrings, the MCs’ tomboy style echoed their audience’s. Salt-N-Pepa emceed full of sass with sexiness, but they never dreamed of playing the racy card like the female MCs to come.

In 1991, the trio’s hit “Let’s Talk About Sex” dealt mainly with a promiscuous woman who regretted the tradeoffs she made sleeping around without love in her life. After the single topped the chart in a few European countries, the group cut “Let’s Talk About AIDS,” directly addressing safe sex and the spread of HIV. By the end of the decade, any female rapper talking about sex would be expected to bypass the social-responsibility message and go straight for the raunchiest angle possible.

Through Salt-N- Pepa, listeners eavesdropped on real talk between liberated young women of the hip-hop generation. Though Hurby Azor produced the bulk of Salt-N-Pepa’s best records, he never presented the group as objects. Salt-N-Pepa always seemed true to themselves, even when treading in the sex appeal of Very Necessary. Shrouded in the colorful Dapper Dan-designed leather jackets and acid-washed jeans of the A Salt With a Deadly Pepa era, their posters still covered the walls of fly guys and girls worldwide.

Through Salt-N- Pepa, listeners eavesdropped on real talk between liberated young women of the hip-hop generation. Though Hurby Azor produced the bulk of Salt-N-Pepa’s best records, he never presented the group as objects. Salt-N-Pepa always seemed true to themselves, even when treading in the sex appeal of Very Necessary. Shrouded in the colorful Dapper Dan-designed leather jackets and acid-washed jeans of the A Salt With a Deadly Pepa era, their posters still covered the walls of fly guys and girls worldwide.

The West Coast continued to rise, with Cali stars like N.W.A, Ice-T, Too Short, MC Hammer and others starting to steal New York’s thunder in the early ’90s. After the flash-in-the-pan success of J. J. Fad’s “Supersonic” in 1990, all eyes turned to Yo-Yo, the hazel-eyed guest MC on Ice Cube’s seminal AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. On an album soaked in misogyny, Yo-Yo traded blow for blow against Cube on “It’s a Man’s World,” and made the most waves of her career a year later with “You Can’t Play With My Yo-Yo.” (“Don’t try to play me out,” she warned). Yo-Yo’s positivist rhymes and self-empowered image landed her memorable cameo roles in Boyz n the Hood, Menace II Society and the Fox sitcom Martin.

The Lady of Rage’s 1994 hit “Afro Puffs” raised sky-high anticipation for her first album. A native Virginian, Rage made her mark with Dr. Dre (“Stranded on Death Row”) and Snoop Dogg (“G-Funk Intro”), as the Above the Rim soundtrack’s “Afro Puffs”—produced by Dre—whet appetites for her Eargasm debut. An MC with top-notch roughneck-rhyme schemes, Rage suffered from an infamous mid-’90s label shakeup at Death Row Records. The fallout between CEO Suge Knight and the exiting Dr. Dre left Rage’s retitled Necessary Roughness severely neglected after its delayed appearance in 1997. A flurry of small acting roles followed, but no more noteworthy music.

The Lady of Rage’s 1994 hit “Afro Puffs” raised sky-high anticipation for her first album. A native Virginian, Rage made her mark with Dr. Dre (“Stranded on Death Row”) and Snoop Dogg (“G-Funk Intro”), as the Above the Rim soundtrack’s “Afro Puffs”—produced by Dre—whet appetites for her Eargasm debut. An MC with top-notch roughneck-rhyme schemes, Rage suffered from an infamous mid-’90s label shakeup at Death Row Records. The fallout between CEO Suge Knight and the exiting Dr. Dre left Rage’s retitled Necessary Roughness severely neglected after its delayed appearance in 1997. A flurry of small acting roles followed, but no more noteworthy music.

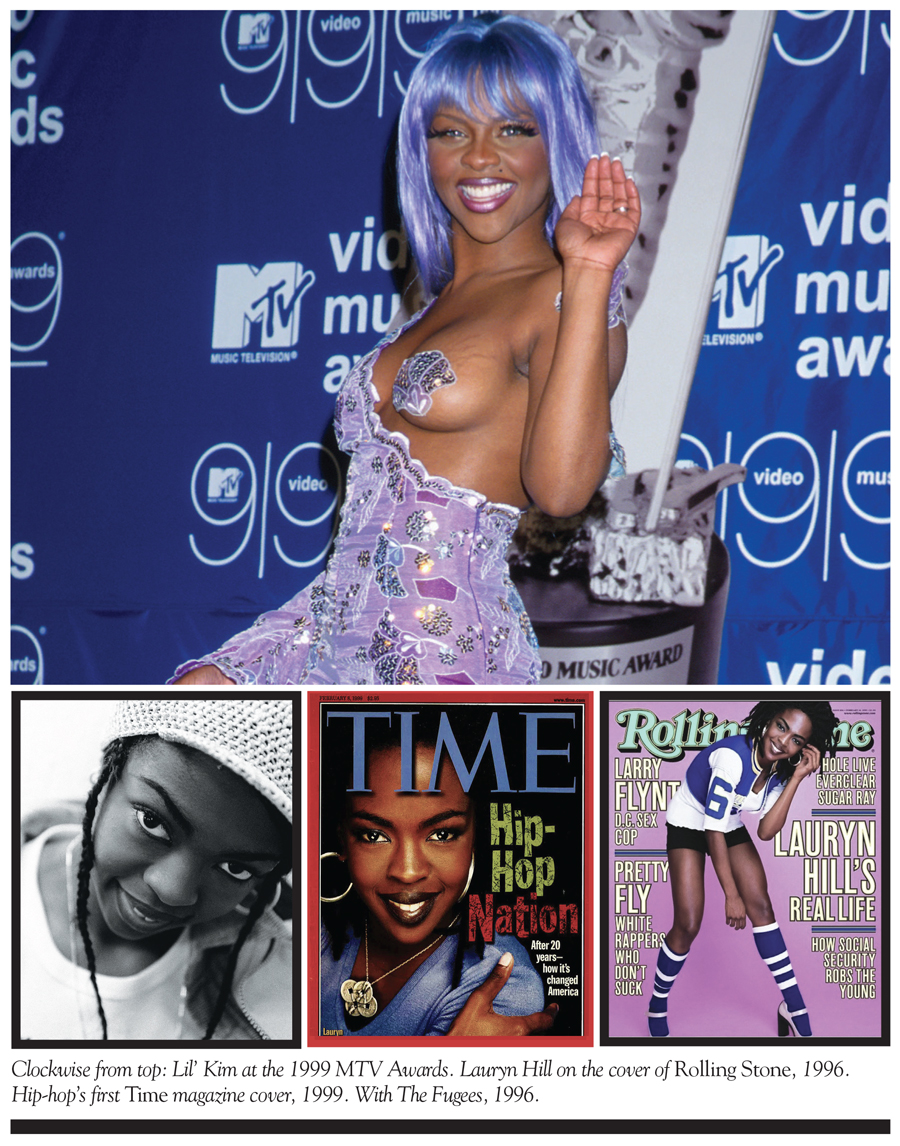

For many, the coming of Lauryn Hill marked the arrival of hip-hop’s living black womanhood (to paraphrase Ossie Davis). Not to discount all the multifaceted variations of black women, but the dreadlocked Lauryn sparked something special in the imagination. By the time the culture’s finest female MC landed the cover of Time magazine in 1999 (a hip-hop first), most were convinced that Lauryn’s worldview covered both the bourgeois and the boulevard in a way that was enticing, relatable and unique to her generation. From her appearance at age 18 on The Fugees’ “Boof Baf” in 1994 to the Grammy-winning The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, so many twentysomething listeners saw themselves in the self-reflective mirror of Lauryn Hill that her phenomenal success seemed practically preordained. Lyricism became more complex with the ladies of hip-hop during the ’90s, and Lauryn definitely surpassed her share of both male and female MCs.

Rap had leapt from the park jam to the arena tour to what FCC chairman Newton Minow once called the “vast wasteland” of television. Fab 5 Freddy and Arsenio Hall brought hip-hop to the boob tube on a regular basis, while Will Smith proved that acting bred a familiarity with audiences that could spread to album sales (and award after award). The black-film renaissance was kind to hip-hop: Spike Lee pumped up tracks by Public Enemy and Arrested Development to enliven his movies, and directors John Singleton and Ernest Dickerson cast MCs as actors to bring in young audiences. Lauryn Hill could act, sing, emcee and produce, a rare quadruple-threat that hip-hop had never before seen.

The economic prosperity ushered in by President Bill Clinton’s administration began to spread across hip-hop as the mid-’90s arrived, personified by Sean “Puffy” Combs, his burgeoning Bad Boy Entertainment and label star Notorious B.I.G. Branches of hip-hop were branding themselves. California claimed gangstas and weed; New York City took hold of Cristal, cash and the player’s lifestyle. Even with Lauryn Hill on the rise in The Fugees, two female MCs were soon to emerge from this new rap worldview who would tilt the paradigm of women in rap irreversibly.

Lil’ Kim beat Foxy Brown to the hip-hop nation by a matter of months in 1995. Born Kimberly Jones in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, the petite MC came up with a coterie of Biggie Smalls associates known as Junior M.A.F.I.A. on the rap sextet’s first single, “Player’s Anthem.” As with Lauryn and The Fugees, fans couldn’t wait for 20-year-old Lil’ Kim to break camp and go solo. The M.A.F.I.A.’s Conspiracy album largely disappointed, but the “Get Money” single certified that Lil’ Kim was no fluke. Her verses were witty, impassioned and graphically sexual; the streets started buzzing about Biggie writing her rhymes.

Lil’ Kim beat Foxy Brown to the hip-hop nation by a matter of months in 1995. Born Kimberly Jones in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, the petite MC came up with a coterie of Biggie Smalls associates known as Junior M.A.F.I.A. on the rap sextet’s first single, “Player’s Anthem.” As with Lauryn and The Fugees, fans couldn’t wait for 20-year-old Lil’ Kim to break camp and go solo. The M.A.F.I.A.’s Conspiracy album largely disappointed, but the “Get Money” single certified that Lil’ Kim was no fluke. Her verses were witty, impassioned and graphically sexual; the streets started buzzing about Biggie writing her rhymes.

Kim grafted a glamourous pop veneer onto the raunchy rhyme content of Too Short and 2 Live Crew, spitting punchlines on par with Dolemite or Moms Mabley. Hip-hop radio DJs around the country spun special versions of Junior M.A.F.I.A. singles, with Kim’s blue bars backspun into a swirl to avoid FCC fines. But stations couldn’t not play the songs; the age of sex rhymes by female MCs had arrived. Lil’ Kim lines about cunnilingus, anal sex and blowjobs—complemented by haute couture, drugs and gunplay—sold 2 million+ copies of her 1996 debut, Hard Core.

Recordings of The Notorious B.I.G. laying down guide vocals for Lil’ Kim tracks like “Queen Bitch” exist on YouTube, evidence that the late Biggie initially wrote her material. (The two had a longstanding romantic relationship.) Still, Ice Cube writing rhymes for Eazy-E is also common knowledge; Jay-Z and Eminem have done the same for Dr. Dre. Lil’ Kim’s delivery and self-assertive persona carried her as far as her rhymes, whoever wrote them. Like a hip-hop Madonna, Lil’ Kim flipped her provocative image into endorsement deals with MAC Cosmetics and Baby Phat, selling another million copies of 2000’s The Notorious K.I.M. sans Biggie’s involvement. By the time Kim won a Grammy for her contribution to the all-star 2001 version of LaBelle’s “Lady Marmalade” (from the Moulin Rouge soundtrack), her rhymes were all her own.

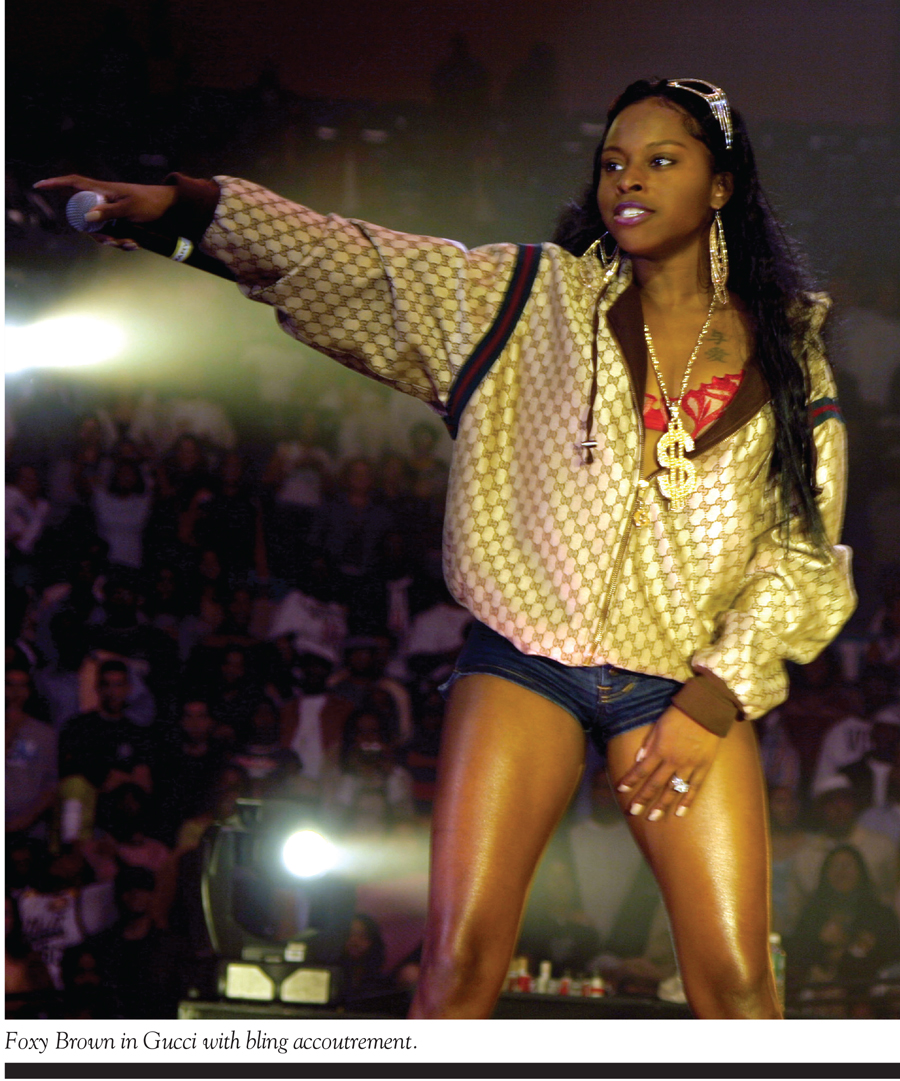

With Junior M.A.F.I.A. dominating the airwaves in late 1995, radio playlists started adding a remix to LL Cool J’s “I Shot Ya!” single featuring Fat Joe, Prodigy, Keith Murray and a new teenage MC who went by the moniker Foxy Brown. Seventeen-year-old Inga Marchand came out the box name-dropping Gucci, Armani and Versace and wouldn’t stop. The Afro-Trinidadian spitfire from Brooklyn popped up months later on Jay-Z’s “Ain’t No Nigga” and then on R&B singer Case’s “Touch Me, Tease Me.” Foxy Brown’s couplets possessed a complexity beyond her years. Plus, her trademark black lipstick and seductive looks jibed perfectly with new cinematic rap-video lensmen like Hype Williams and Director X.

With Junior M.A.F.I.A. dominating the airwaves in late 1995, radio playlists started adding a remix to LL Cool J’s “I Shot Ya!” single featuring Fat Joe, Prodigy, Keith Murray and a new teenage MC who went by the moniker Foxy Brown. Seventeen-year-old Inga Marchand came out the box name-dropping Gucci, Armani and Versace and wouldn’t stop. The Afro-Trinidadian spitfire from Brooklyn popped up months later on Jay-Z’s “Ain’t No Nigga” and then on R&B singer Case’s “Touch Me, Tease Me.” Foxy Brown’s couplets possessed a complexity beyond her years. Plus, her trademark black lipstick and seductive looks jibed perfectly with new cinematic rap-video lensmen like Hype Williams and Director X.

Def Jam dropped Foxy Brown’s Ill Na Na in November 1996, just seven days after Lil’ Kim’s Hard Core. Both sold millions, adding new classics like “No Time,” “Big Momma Thang” and “I’ll Be” to the lexicon of women’s rap. Foxy’s follow-up, Chyna Doll, took the #1 chart spot in 1999; she was the first female MC to do so without singing. Foxy’s rumored romance with Jay-Z set tongues wagging about possible ghostwriting behind the scenes. Gossips said the same when she joined The Firm supergroup in ’96 alongside Nas, AZ and Nature. Whatever the case, hip-hop America’s appetite for both Lil’ Kim and Foxy Brown said something new about the culture.

The bling era was beginning, and female MCs who lacked sex appeal were relegated to the sidelines. Rap as a serious music-label rainmaker meant doing whatever it took to sell product. Women MCs entering the game then who relied on lyrical skills above glamour or sexual magnetism—Bahamadia, Heather B, Rah Digga and more—couldn’t move units anywhere near Kim or Foxy’s level. (One exception, Da Brat, was the first female rapper to go platinum in 1994 with Funkdafied. She sold another million with 2000’s Unrestricted.) After the one-two punch of Hard Core and Ill Na Na, seductiveness in female rap became an essential part of the package. Essential, that is, until the arrival of the next supa-dupa-fly MC.

In the summer of ’96, Missy Elliott grabbed listeners with her infamous onomatopoeic aside (“Hee hee hee hee how…”) on a Puff Daddy remix of “The Things You Do,” by R&B one-hit wonder Gina Thompson. A string of guest slots with other artists built buzz for the 25-year-old rapper, who would soon write and produce music as an emcee. As a teenager in Portsmouth, Virginia, young Melissa Elliott was a childhood friend of Timothy “Timbaland” Mosley, and they burst onto the scene as a tag team working with R&B singers Ginuwine and Aaliyah.

Missy’s 1997 Supa Dupa Fly debut led with “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)”—a mesmerizing, synth-dappled deconstruction of Ann Peebles’ R&B gem, “I Can’t Stand the Rain,” and had nothing whatsoever to do with sex, seduction or even lyrical intricacies. Missy sidestepped all of that with the sheer innovation of her sound, and inventive video collaborations with director Hype Williams. Her rhymes were playful and elementary, a throwback to 1980s freestyle rap. But the futuristic breakbeats Missy and Timbaland recorded for Supa Dupa Fly, Da Real World (1999), Miss E…So Addictive (2001) and beyond prepared hip-hop for the 21st century. Eclectic to say the least, Missy embraced trip-hop, bhangra, drum ’n’ bass and old-school rap in the sound of her albums.

Bypassing the sexual mandate of the moment, Missy Elliott slowly became the best-selling female rap artist of all time, with five platinum albums from Supa Dupa Fly to 2005’s The Cookbook. She also arguably became the most successful female producer in music history to date, her huge production discography including Mariah Carey, Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston and Mary J. Blige—as well as Yo-Yo, Trina and MC Lyte on the hip-hop side. Missy had a hustle outside of rapping, which enhanced her overall success.

The multitalented Queen Latifah could relate. An Afrocentric MC of the Flavor Unit posse who was also associated with the Native Tongues school, she radiated intelligence and positivity. Latifah also shared a vision of female empowerment on cuts like “Ladies First,” which featured fellow distaff rapper Monie Love. But the New Jersey-bred rapper born Dana Owens would soon be discovered for her other gifts. Director Spike Lee cast the queen in her first film role in Jungle Fever in 1991; fans would remember her judging a DJ competition in Juice a year later. The Black Reign album, her third, spawned two hits in the Grammy-winning “U.N.I.T.Y.” and “Just Another Day…” come late ’93. But Latifah had already started filming the Fox sitcom Living Single that summer, which premiered in August and continued for five seasons, only a year less than The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

The multitalented Queen Latifah could relate. An Afrocentric MC of the Flavor Unit posse who was also associated with the Native Tongues school, she radiated intelligence and positivity. Latifah also shared a vision of female empowerment on cuts like “Ladies First,” which featured fellow distaff rapper Monie Love. But the New Jersey-bred rapper born Dana Owens would soon be discovered for her other gifts. Director Spike Lee cast the queen in her first film role in Jungle Fever in 1991; fans would remember her judging a DJ competition in Juice a year later. The Black Reign album, her third, spawned two hits in the Grammy-winning “U.N.I.T.Y.” and “Just Another Day…” come late ’93. But Latifah had already started filming the Fox sitcom Living Single that summer, which premiered in August and continued for five seasons, only a year less than The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

Serious starring parts eventually led to her 2002 Oscar nomination for playing Mama Morton in Chicago. Though Order in the Court met with disappointing sales in 1998, Queen Latifah was already becoming a household name in Hollywood. A singer going way back to her ’89 debut, All Hail the Queen, she eventually released two albums featuring jazz vocals, including the Grammy-nominated The Dana Owens Album.

In 1999, the same year that saw The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill pick up an Album of the Year award at the Grammys and Foxy Brown’s Chyna Doll debut at the top of the album charts, Philly rapper Eve debuted at #1 with Let There Be Eve…Ruff Ryders’ First Lady. The last of the female MCs to be introduced before the coming dawn of Napster and the downturn of the economy post-9/11, Eve blended sexual charisma with hardcore rap skills. After charting hits like “Gotta Man” and “Let Me Blow Ya Mind” with pop singer Gwen Stefani, Eve showed the world her acting chops. Following her star turn in the 2002 comedy Barbershop, she landed her own self-titled sitcom the next year on UPN (with theme music by Missy Elliott).

Miles Marshall Lewis (@MMLunlimited) is the Harlem-based author of the upcoming Promise That You Will Sing About Me: The Power and Poetry of Kendrick Lamar, and his writing has appeared in Billboard, Rolling Stone, GQ and elsewhere.

Miles Marshall Lewis (@MMLunlimited) is the Harlem-based author of the upcoming Promise That You Will Sing About Me: The Power and Poetry of Kendrick Lamar, and his writing has appeared in Billboard, Rolling Stone, GQ and elsewhere.

NOW LISTEN

NEAR TRUTHS: EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED

One name keeps popping up amid the Roan-related speculation. (11/26a)

| ||

NOW WHAT?

We have no fucking idea.

COUNTRY'S NEWEST DISRUPTOR

Three chords and some truth you may not be ready for.

AI IS ALREADY EATING YOUR LUNCH

The kids can tell the difference... for now.

WHO'S BUYING THE DRINKS?

That's what we'd like to know.

|

to Terms and Conditions