BLACK MUSIC MONTH: HOW "MOTHER OF THE MIC" MC SHA-ROCK BIRTHED A GENERATION

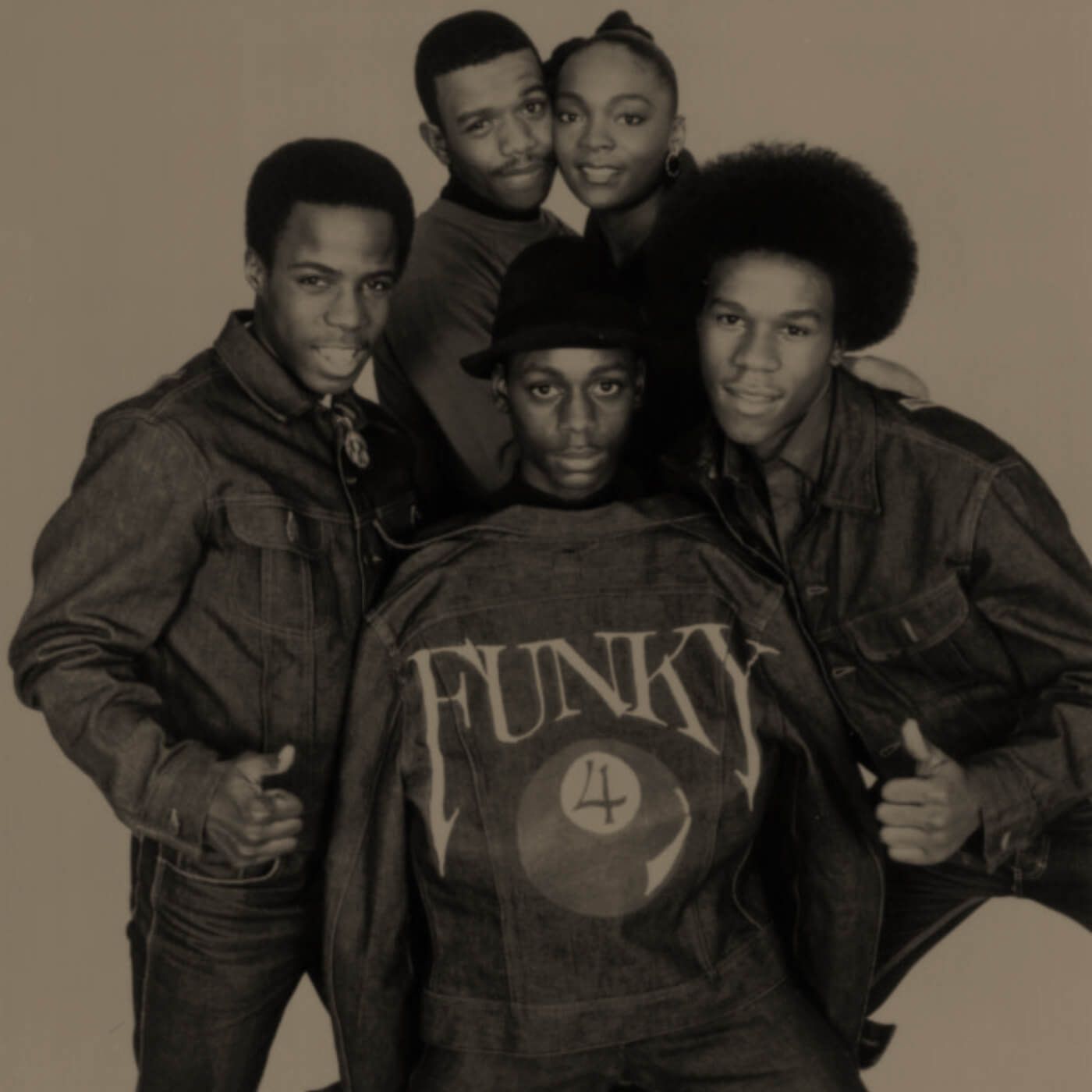

It was Feb. 14, 1981, and Blondie’s Debbie Harry was hosting Saturday Night Live. Between sketches starring cast members Eddie Murphy and Gilbert Gottfried, the über-cool chanteuse introduced “the best street rappers in the country” to an unsuspecting audience. Bronx natives Funky 4 + 1 thus became the first hip-hop group to appear on national television, performing their single “That’s the Joint.”

It was Feb. 14, 1981, and Blondie’s Debbie Harry was hosting Saturday Night Live. Between sketches starring cast members Eddie Murphy and Gilbert Gottfried, the über-cool chanteuse introduced “the best street rappers in the country” to an unsuspecting audience. Bronx natives Funky 4 + 1 thus became the first hip-hop group to appear on national television, performing their single “That’s the Joint.”

They were also the only widely known rap group with a female member, MC Sha-Rock, 18 at the time.

Always ahead of her time, Harry kept her ear to the street. In November 1979, the Funky 4—as it was then known―released its debut single, “Rapping and Rocking the House,” on Enjoy Records. By 1980, the act had signed with Sylvia and Joe Robinson’s Sugar Hill Records, home to The Sugarhill Gang, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five and the Treacherous Three.

The Funky 4 was invited that year to play a show at The Kitchen, a seedy punk-rock club in Chelsea. “This girl invited us to perform at The Kitchen,” Sha-Rock remembers. “We became the first rap group to play for a different audience―we had all the punk-rock kids going crazy over hip-hop. The girl who booked us happened to be friends with Debbie Harry.”

Harry was looking for the best rappers in the city to perform on SNL. She knew she would be taking a risk presenting an all-Black group performing a new form of music for a mostly white audience. But she was intrigued by Sha-Rock’s presence.

“She could have gone with Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, but Debbie chose us because we were young-looking, innocent and one of the baddest MC groups—with a female,” Sha-Rock says. “She is the person who really set it off for hip-hop culture as far as television, and she allowed the world to see what we were doing back in the Bronx. She brought that to the forefront.”

Heralded as the Mother of the Mic, Sha-Rock is widely recognized as hip-hop’s first female MC.

Born Sharon Green in Wilmington, N.C., she bore witness to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. But racial tension wasn’t the only difficulty she faced; her father, a longshoreman who often spent days at sea, abused her mother. “He was very controlling,” she says. “He fought her all the time and would bruise her up.”

One fateful day, her mother finally fled, taking her five children with her. Though they tried to hide from him, her husband soon discovered their location and learned his estranged wife was with another man. Enraged, he broke in through a window and began pummeling him. At one point during the altercation, Sha-Rock’s father bit the man’s ear off. “He was Mike Tyson before Mike Tyson was Mike Tyson,” Sha-Rock says with a laugh, the event clearly softened by time. “We had to run miles to my grandmother’s house. My mom had nine brothers, and they wanted revenge. After that, my father disappeared to Florida and my mom moved back to the projects.”

But when Sha-Rock was eight, her mother loaded the kids onto a Greyhound bus bound for New York, hoping the city would be diverse enough to provide sanctuary. Despite her efforts to shield her family from the racism she’d experienced growing up in the South, there was no escaping it. Sha-Rock remembers feeling eyes on her when she walked into a store. It was not lost on her that she was treated differently from her white peers. “My mom wouldn’t let us out of her sight,” Sha-Rock says. “We weren’t allowed to do any activities outside of school.”

But when Sha-Rock was eight, her mother loaded the kids onto a Greyhound bus bound for New York, hoping the city would be diverse enough to provide sanctuary. Despite her efforts to shield her family from the racism she’d experienced growing up in the South, there was no escaping it. Sha-Rock remembers feeling eyes on her when she walked into a store. It was not lost on her that she was treated differently from her white peers. “My mom wouldn’t let us out of her sight,” Sha-Rock says. “We weren’t allowed to do any activities outside of school.”

They initially lived at her uncle’s one-bedroom apartment in Harlem, but in 1971, Sha-Rock’s mother moved the family to the Bronx and enrolled young Sharon in talent shows at a nearby community center, where the youngster also wrote poetry.

In August 1973, Jamaican DJ Kool Herc and his sister, Cindy Campbell, hosted their now-legendary “Back to School Jam” at 1520 Sedgwick in the Bronx—an event subsequently mythologized as the birth of hip-hop. Sharon was still only 13, though, so her mother refused to let her go to any of Kool Herc’s parties.

Abandoned buildings littered the boroughs, the crime rate was exploding and poverty was omnipresent. But hip-hop was becoming a beacon in the darkness.

It was everywhere—speakers blared from the parks, DJs lugged their records to parties, MCs rapped on the mic and dueled on streetcorners, subway cars were festooned with new-school graffiti, breakdancing spawned fierce collectives like the Rock Steady Crew and Zulu Kings. In 1976 Sha-Rock herself ventured into breakdancing.

A year into her tenure as a “B-girl,” she spotted a flyer posted by someone looking for an MC. She jumped on the number 41 bus and wrote a few rhymes in transit to use for the audition. And that’s how Sha-Rock, along with K.K. Rockwell, Keith Caesar and Rahiem—who would later join Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five—became the founding members of the Funky 4. By 1978, the group had its first record deal.

“Rap music was getting ready to go commercial,” Sha-Rock recalls. “People were hearing about us through cassette tapes, by word of mouth and from flyers. That was a core element of how we communicated in hip-hop culture. When Debbie got us on Saturday Night Live, she didn’t lie—we were one of the most prominent groups in the city and were setting the standard for what MC and DJ culture was.”

Hip-hop had begun to achieve a foothold in the mainstream in 1979 when “Rapper’s Delight” by The Sugarhill Gang became the first rap song to crack the Top 40. It was helped along by TV and movies and pop acts like Blondie (whose 1981 #1 hit “Rapture” would demonstrate the band’s status as genuine fans of the burgeoning genre).

During those years, Sha-Rock was on more flyers than any other woman in hip-hop. “I was the first female MC to be part of rap battles, and I have the flyers to prove it,” she confirms. “I was the first female MC to create rap battles. I was the first female MC to perform at the Audubon Ballroom. I was the first female MC to perform for other audiences, outside of hip-hop venues. I was the first female MC to get a record deal. I was the first authentic female MC from the streets of New York City who helped create the culture. I was the first female MC on television and the first to use an echo chamber.”

To this day, Run-DMC’s Darryl “DMC” McDaniels credits Sha-Rock for teaching him about the echo chamber, a studio technique used to produce reverb. “He told [Run-DMC DJ] Jam Master Jay he wanted to sound like Sha-Rock on the echo chamber. It just blows my mind. I will always love him and commend him for that,” she says. “Run-DMC, the most prominent group in hip-hop culture…for him to say I inspired him as a rhymer and I inspired him and [Rev] Run to do the echo chamber, is just incredible.”

Though Sha-Rock was an original member of the Funky 4, following a hiatus from the group she became the “+ 1.” Rahiem had left for the Furious Five, so he and Sha-Rock had been replaced. When she returned, however, she didn’t feel like the “+ 1” was a slight or that it implied that women in hip-hop were some kind of nameless afterthought. Rather, she felt it singled her out and illustrated her impact. “Grandmaster Flash came up to me once and said, ‘You were the only female out there that was running with all of us.’ In that era, I had power as a female MC.”

With celebrations of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary underway, Sha-Rock is being recognized as one of rap’s pioneers—and claiming her legacy. Over the years, people have come for her crown in an attempt to diminish her accomplishments. “I had to learn the hard way,” she explains. “I was always trying to be humble so I didn’t come across as arrogant. But then I thought, ‘No. I’m not going to allow history to be rewritten; I’m going to tell and show my story—with receipts.”

To that end, she published 2010’s The Story of the Beginning and End of the First Hip Hop Female MC. She encouraged those unfamiliar with the origins of hip-hop to do their homework and understand its roots, especially when it comes to Black women. From Cindy Campbell and Sylvia Robinson to MC Sha-Rock and Roxanne Shanté, they’ve been present since hip-hop began, breaking down barriers once thought impenetrable and demonstrating what was possible.

SNL breakthrough “That’s the Joint,” meanwhile, was deemed the best song of the ’80s by Robert Christgau in the Village Voice. In his initial review, the esteemed music critic wrote: "The rapping is the peak of the form… Quick tradeoffs and clamorous breaks vary the steady-flow rhyming of the individual MCs, and when it comes to Sha-Rock, Miss Plus One herself, who needs variation?” “Joint” has been sampled by no less than De La Soul (“Say No Go” from 3 Feet High and Rising) and the Beastie Boys (“Shake Your Rump” and “Shadrack” from Paul’s Boutique).

Last year, Sha-Rock joined the Visual Communication & Digital Media Arts program at Maryland’s Bowie State University as an adjunct professor, hip-hop historian and resident MC. With this platform, the SiriusXM show “Rock the Bells,” her book and more, she continues to nurture and educate the culture—just as you’d expect from the Mother of the Mic.